Credit: Josh Lopez

Back in 2008, former vice president Al Gore decided that it was time to take the fight against climate change to a new level. Speaking at the annual meeting of the Clinton Global Initiative, Gore said that the world had “reached the stage where it is time for civil disobedience,” and called for young people to take the lead. The fight against global warming wasn’t just a technological or political challenge to Gore and his allies. It was a moral one—and it needed to be fought with the same tactics of protest used by the antiwar or civil rights movement.

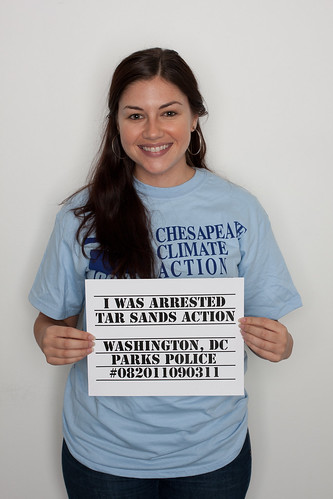

Those tactics have been on display in Washington this weekend, where scores of people have been arrested in front of the White House in an ongoing protest urging President Obama to block construction of the proposed Keystone XL pipeline, would bring crude oil from western Canada’s oil sands developments to the U.S. Those arrested include dozens of the sort of young people Gore has called for, but also grizzled greens like the writer and activist Bill McKibben—founder of the international climate advocacy group 350.org—and Gus Speth, the chair of the U.S. Council on Environmental Quality under former President Jimmy Carter.

Here’s how McKibben described the aims of the protests—set to continue for the next two weeks—in the Washington Post last week:

The issue is simple: We want the president to block construction of Keystone XL, a pipeline that would carry oil from the tar sands of northern Alberta down to the Gulf of Mexico. We have, not surprisingly, concerns about potential spills and environmental degradation from construction of the pipeline. But those tar sands are also the second-largest pool of carbon in the atmosphere, behind only the oil fields of Saudi Arabia. If we tap into them in a big way, NASA climatologist James Hansen explained in a paper issued this summer, the emissions would mean it’s “essentially game over” for the climate.

A little background: while there are many groups unhappy about the Keystone XL pipeline itself—mostly because of the fear of spills, which former TIME intern Tara Thean explained in this post—the real target of the Washington protesters is the oil sands development itself. (McKibben and other environmentalists call it “tar sands,” while industry and government usually call the deposits “oil sands.” The latter to me seems a little less pejorative.) As the NASA climatologist and activist James Hansen has pointed out, the sheer size of the Canada’s oil sands reserves—nearly 200 billion barrels of oil are believed recoverable, second only to Saudi Arabia’s remaining reserves—means they hold a lot of carbon, enough to significantly warm the atmosphere if burned, as Hansen has written:

The tar sands of Canada constitute one of our planet’s greatest threats. They are a double-barrelled threat. First, producing oil from tar sands emits two-to-three times the global warming pollution of conventional oil. But the process also diminishes one of the best carbon-reduction tools on the planet: Canada’s Boreal Forest.

Hansen is comparing oil sands crude to the conventional black stuff that might come from Saudi Arabia or Venezuela, where oil is relatively cheap to pump from the ground. Not so in Alberta—oil sands development initially resembled strip mining, carving out vast chunks of forest to essentially burn the oil from the sands in a process far more destructive than crude exploration elsewhere. I’ve visited the territory around Alberta’s Fort McMurray, home to the oldest oil sands development, and from a helicopter the landscape looks like something out of Tolkien—the fires of Mordor. While that part of Canada is lightly populated, a First Nations community—native Canadians—that lives on the bank of the Athabasca River, downstream from the oil sands developments, has complained about high rates of cancer they blame on pollutants from the mining.

Canadian energy companies argue that they’ve managed to reduce the impact of oil sands mining in recent years, and indeed, I did see new developments that were done in situ—pumping steam deep into the ground, which heats the sands into a viscous liquid, allowing them to be pumped to the surface like conventional oil. The result isless deforestation and less pollution—most of the work happens under ground. But even the newer, cleaner methods still result in significant greenhouse gases—more so than conventional petroleum production—because of the need to use energy to get at those oil sands. As a new report from Canada’s Environmental Ministry shows, if the country’s oil sands productions doubles as expected over the next decade, greenhouse gas emissions from the oil and gas sector will rise by nearly one-third between 2005 and 2020, while Canada will lose the carbon-sequestering benefit of 740,000 ha of boreal forest.

Of course, there’s nothing President Obama can do to stop Canada from mining—and shipping—its oil sands crude. (And there’s no indication the Canadians will stop—Canada’s conservative government is dominated by western energy interests, and even though the country is blowing through its Kyoto carbon-cutting targets, it’s full speed ahead on oil sands.) But by blocking the Keystone XL pipeline—which the State Department would need to do by the end of the year—would complicate oil sands development, and send wary environmental voters the signal that Obama still cares about climate change.

But climate change aside, Canadian oil sands have one major advantage—they’re Canadian. Our friendly neighbors to the north are actually our biggest petroleum dealer, and their oil comes without the rather messy geopolitical tangles of Mideast crude. In a 2009 report for the Council on Foreign Relations, Michael Levi argued that the security benefits of oil sands production probably outweighs the environmental costs, at least in the short-term. Whatever oil we refuse to buy from Canada will likely just be replaced by politically risky crude from the Middle East or Russia or Venezuela—or perhaps, by environmentally riskier developments in the Niger Delta or the Alaskan Arctic. While blocking the Keystone XL pipeline would slow the development of oil sands, it wouldn’t stop it. Oil is a fungible commodity, and if the price goes high enough—and there’s little reason to expect it wouldn’t—eventually Canada would sell that crude elsewhere, perhaps piping it to the west coast and shipping it to a thirsty China, even if that is more expensive and difficult than simple selling it to the U.S.

I think that the only way that we’ll ever truly kick the oil habit is from the demand side, not the supply side—by encouraging conservation through greater fuel efficiency, and by developing superior alternatives. That hasn’t happened yet—last year global oil consumption hit an all-time high of 87.4 million barrels a day, and barring another global slowdown, there’s little reason to expect that it will fall. I understand—and commend—why McKibben and his brave colleagues have put their freedom on the line, but I worry that the oil sands are going to be burned no matter what Obama does, and it’s wrong to make the pipeline a climate red line for Obama. (As my colleague Michael Grunwald wrote recently, Obama has done a lot more for greens than they may realize.) It might be better to make a deal for the pipeline—investment in alternative energy or fuel efficiency standards in exchange for Canadian oil sands.

If we’re going to protest something, better to protest new and existing coal plants, which are responsible for more U.S. carbon emissions than any other source—and which are much easier to replace than oil. And even better, greens are already succeeding in their fight against coal—in the boardroom and on the streets, with programs like the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal. Al Gore would be proud.

Bryan Walsh is a senior writer at TIME. Find him on Twitter at @bryanrwalsh. You can also continue the discussion on TIME’s Facebook page and on Twitter at @TIME.